Thought as word dynamics. II. Architecture (5)

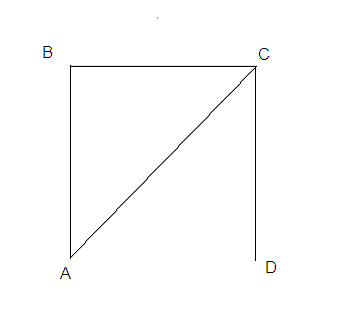

Mathematically speaking, a graph is a set of ordered pairs. It can be decomposed in elementary units of individual pairs. Each of the two elements in an ordered pair represents a node in the graph and every pair represents an edge. Say, there are four nodes, A, B, C and D and the graph is defined as (a, b), (b, c), (c, d) and (a, c), the corresponding graph is as represented in the figure below.

An example of a word-pair is “cat-feline” and each of the two words “cat” and “feline,” can be part of more than one of such pairs: “feline” may be associated again, this time with “mammal,” and “cat” with “whiskers,” etc. The individual units of the network we’re talking about here are two nodes associated and standing for “word-pairs.”

The origin of the medieval notion of the “categoreme” introduced in Section 4 rests in Aristotle’s short treatise called “Categories” devoted to those words that can act as either a subject or a predicate in a sentence. “Blue” is predicated of the subject “violets” when I say that “violets are blue.” Color” is predicated of “blue,” the subject, when I say that “Blue is a color.” It is clear that the words so distinguished as being able to act either as subject or as predicate amount to those I called in Section 4 “content-words.” Why call them then “categoremes”? Because, Aristotle argues, they can be used in ten different ways, acting in ten different functions, being also the ten standpoints from which “stuffs” can be envisaged. These are the “various meanings of being” which he calls the categories.

Here is his explanation of this in his own terms: “Expressions which are in no way composite signify substance, quantity, quality, relation, place, time, position, state, action, or affection. To sketch my meaning roughly, examples of substance are ‘man’ or ‘the horse’, of quantity, such terms as ‘two cubits long’ or ‘three cubits long’, of quality, such attributes as ‘white’, ‘grammatical’. ‘Double’, ‘half’, ‘greater’, fall under the category of relation; ‘at the market place’, ‘in the Lyceum’, under that of place; ‘yesterday’, ‘last year’, under that of time. ‘Lying’, ‘sitting’, are terms indicating position, ‘shod’, ‘armed’, state; ‘to lance’, ‘to cauterize’, action; ‘to be lanced’, ‘to be cauterized’, affection. No one of these terms, in and by itself, involves an affirmation; it is by the combination of such terms that positive or negative statements arise. For every assertion must, as is admitted, be either true or false, whereas expressions which are not in any way composite such as ‘man’, ‘white’, ‘runs’, ‘wins’, cannot be either true or false” (Aristotle, Categories, IV).

The final words in the passage just quoted are most important: isolated terms, terms taken on their own cannot be regarded as either true or false: “it is by the combination of such terms that positive or negative statements arise.” It is possible to even go one step further: does a term in isolation mean anything? “Of course” is one tempted to say, indeed, as I said earlier, we’re at no loss when asked to define a term like “rose.” I gave as an example of doing precisely that: “a rose is a flower that has many petals, often pink, a strong and very pleasant fragrance, a thorny stem.” We spontaneously assigned to the rose the category of substance, of being a flower; we assigned quantity to its petals for being many; we attributed the quality of being pink to its petals, etc. In other words, we brought the rose out of its isolation by connecting it with other words in sentences of which, as Aristotle observed, it will then be possible to say if they are true or false.

Out of the examples the Greek philosopher mentions, it is self-evident that “double,” “half,” “greater,” “two cubits long,” “lying,” “sitting,” “shod,” “armed,” “runs,” “wins” have no meaning unless they are said – predicated – of something else. But with a moment of reflection it becomes obvious that this applies to the other words too: “man,” “horse,” “white.” As we’ve just seen when examining what is called the definition of a rose, these words also need to be said of something to come alive. In a passage of one of his dialogues, The Sophist, Plato has the Stranger from Elea (*) make an identical point: “The Stranger: A succession of nouns only is not a sentence, any more than of verbs without nouns. […] a mere succession of nouns or of verbs is not discourse. […] I mean that words like ‘walks,’ ‘runs,’ ‘sleeps,’ or any other words which denote action, however many of them you string together, do not make discourse. […] Or, again, when you say ‘lion,’ ‘stag,’ ‘horse,’ or any other words which denote agent – neither in this way of stringing words together do you attain to discourse; […] When any one says ‘A man learns,’ should you not call this the simplest and least of sentences? […] And he not only names, but he does something, by connecting verbs with nouns; and therefore we say that he discourses, and to this connection of words we give the name of discourse” (Plato, The Sophist).

Assuming that there is in the brain a network being the substrate for speech performance, what would then be the “element” – the smallest unit – to be stored in such a network? I hold that it would be the “word-pairs” just described, instead of words in isolation. Synaptic connections seem the perfect locus for such storage: the place where the building blocks of the brain’s biological network, the neurons, come together. Why not the isolated word? Because, as Aristotle saw it sagaciously, “word-pairs” are true or false and, as we will see next, something being true or false is the first condition for it having an affective value, i.e. what brings in motion the dynamics of speech performance.

(*) Griswold notices that – apart from Parmenides – the anonymous stranger is the single figure in all the dialogues who speaks like a full-blown philosopher; he observes also that while Socrates is present in the Sophist he remains almost mute (Charles L. Griswold, “La naissance et la défense de la raison dialogique chez Platon,” in La naissance de la raison en Grèce, Paris: PUF, 1990: p. 365)

One response to “The individual unit in the network as far as speech generation is concerned is a word-pair”

Hi Paul,

Other pairs are possible, combining A And D for exemple (or D And B)

DA or DB are possible Edges in Euclidian geometry.

If not in your theory, would you say it s because it is based on a non Euclidian geometry ?

Or because Nodes And Edges are an easy way to figure concepts, but have no geometrical meaning ?

Or at last, other possibilities i did not mentionned ?

Thanks a lot for increasing our knowledge with such “understandable” article