I’m working on the paper to be given at the Human Complex Systems’ one-day conference on March 8th. I don’t want to divulge prematurely any scoop but at the same time I’d like to share some of my puzzlement as I go, and as if thinking aloud.

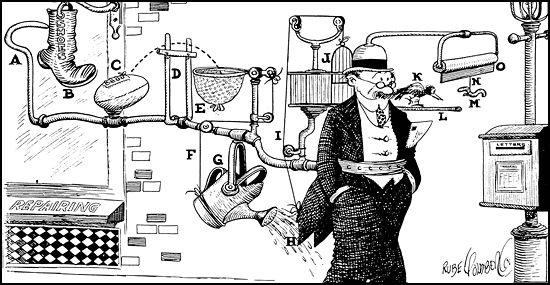

To recap: I’m toying with the concept of a large – as complex as need be – model of the subprime crisis. The easy parts are those which are already modeled of that Rube Goldberg machine (see diagram), like the cash flow structure (of variable complexity) of the financial instruments at the epicenter of the crisis, i.e. Asset-Backed Securities (complex); Collateralized Debt Obligations (complex); Asset-Backed Commercial Paper (simple) and Credit-Default Swaps (simple).

But of course as soon as I’ve claimed that these financial instruments are truly modeled, a number of caveats come to my mind:

1) Some assumptions in these models are deemed “subjective.”

2) Many of these models make wild and unwarranted assumptions about the feasibility of forecasting the future.

3) However accurate the models might be, those human agents who make decisions from them

— a. understand them in most cases only partially;

— b. make errors when using them – even when they fully understand them.

Let me review this in that order:

1) “Subjective” assumptions: that means that there’s a range of possible values and one is assigned as the outcome of the data having been processed by the “human cognitive cocktail” – see below.

2) Knowing the future: about some of these models that feel confident at the validity of their wild forecasts, there is “industry consensus” in finance about that feasibility; to give just one example: the forward yield curve is erroneously assumed to hold information about the future (spot) yield curve. What exactly does “industry consensus” mean in this instance? That people use the model because they either a) mistakenly believe it to be “scientific,” i.e. true?; b) do suspect it might not be true but use it anyway because of its “investment-grade” industry standard rating? Does it matter for any practical purpose if either a or b is the case?

3) Agent’s understanding of the model used.

— a. Partial understanding of the model only: it probably just means that agents’ decision-making is loosely linked to the model’s outcome if understanding is minimal and tightly linked to it if it is fair; the decision is a function of the model’s results plus minus a huge or a small epsilon (*) respectively.

— b. Error when using the model: just epsilon.

Returning to the “human cognitive cocktail,” I call “human cognitive cocktail,” the methods used by human agents in puzzle-solving (the following list is likely to be revised and refined – its order is arbitrary):

1. “Fuzzy logic type” of probability calculus.

2. “Expert-system-like” combination of logical rules.

3. “Logistic regression type” of multi-factorial pseudo-quantitative processing.

4. “Multi-layered perceptron type” of pure (= unconscious) intuition.

(To be continued…)

(*) Greek letter traditionally used as a symbol for the error factor.

3 responses to “Agents using financial models and the “human cognitive cocktail””

[…] « Agents using financial models and the “human cognitive cocktail” 20 02 2008 […]

??????? ?? ??????????????, ?????????? ?????????? ??????????? ???? ???????? ? ???.

??????? ?????, ??? ???????????. 🙂 ??????? ??? ? ???????….